"It is Not Legend For Them, It Is Factual": Author Aashisha Chakraborty On Writing Fantasy Fiction About Rani Gaidinliu

- sevensistersarchive

- Feb 4, 2024

- 5 min read

The stories and legends revolving around “Rani” Gaidinliu Pamei have been documented by various people. Writings by Som Kamei, A.K. Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru (who first bestowed her with the title of ‘Rani’) have been in the public domain since pre-Independent India.

However, in 2023, bestselling author Aashisha Chakraborty rewrote Rani Gaidinliu’s story through a book titled ‘The 13-Year Old Queen And Her Inherited Destiny.’ What separates this from most re-tellings is her use of ‘historical fantasy fiction’—a genre that is gaining traction in India’s publishing scene.

It may be analogous to Amish’s Shiva Trilogy or Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Palace of Illusions. The notable exception is that Aashisha’s book does not concern mythological fiction; it concerns historical fiction.

This is doubly curious in the case of Gaidinliu’s history. For even the history of Gaidinliu’s life is mired in legend, fable, and oral tradition. Where does one draw the line between history and legend? What is fantasy, and what is truth?

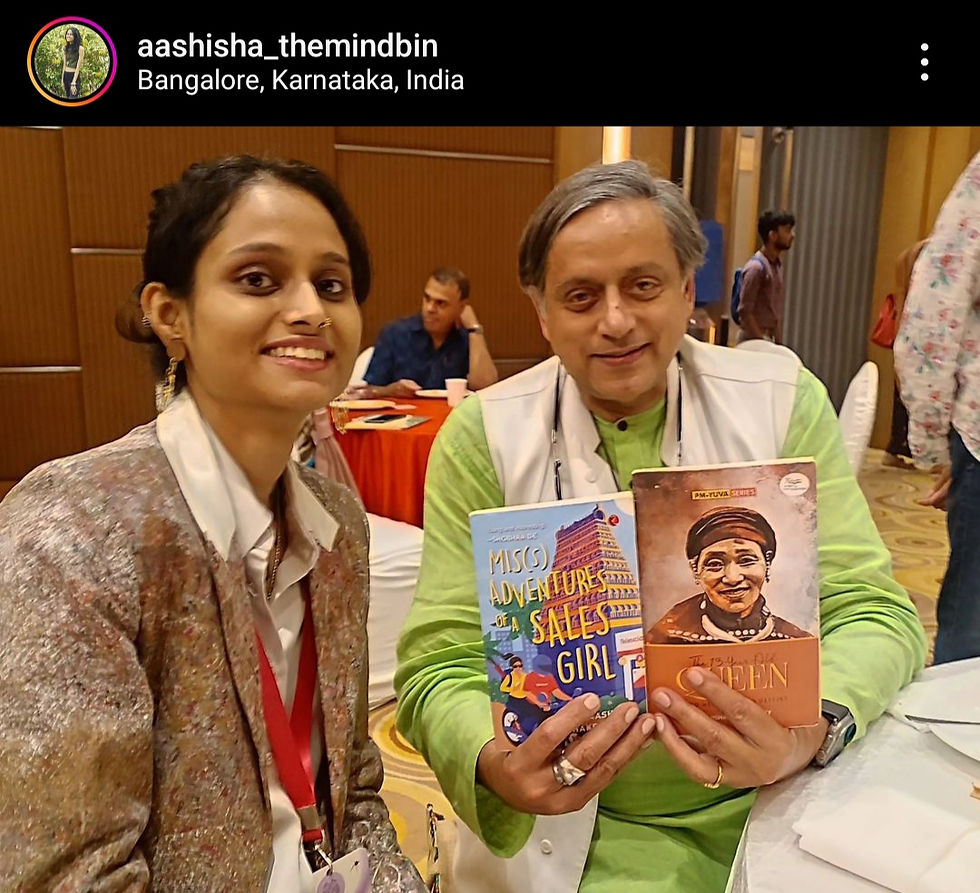

Aashisha and I found a moment to chat in the swirling chaos of the Bangalore Literature Festival in December 2023. She shared with me her experience as a born-and-bred Delhiite, who chose to write a story that was close to the sentiments of the peoples of Nagaland, Manipur and Assam; a region which is close to her hometown of West Bengal.

Here’s how it went.

Q: How did the idea to write a story about a Northeast freedom fighter come to mind?

“I was given the opportunity to write a book about any freedom fighter through the Pradhan Mantri YUVA Yojana Scheme. They have an implementation agency called the National Book Trust. The only mandate I was given was to bring ‘unsung heroes’ to light.

“I knew almost every major state/city had a famous local hero or freedom fighter. But I started from the East, because that’s where my roots are. I have a few relatives in Agartala and Assam, although I’ve never really stayed there. My idea was to figure out what prompted young children to take up causes that lead them to sacrifice their entire lives. Young freedom fighters became my focus, and it was after a decent amount of research that Rani Gaidinliu caught my eye. She had deep ties with nature and had also started rebelling as a child. Honestly, she was one of those bold women at a time when feminism as a concept or movement had not even gained traction.”

It must not have been easy for a Delhiite to write about a freedom fighter based in the Northeast.

“Yes, but Northeast is very less explored and understood, so I felt I had to do it. For research, I went into archival documents. I visited the British Council Library, the Nehru Centre and the like. The E-Pao archives helped me a lot. For example, I thought the word ‘genna’ meant ‘festival’, but after a good amount of reading, I realized that it had a lot to do with rituals. It actually means ‘prohibition’ - not just on alcohol, but also on cooking, intimate activities, and things like that!

“My biggest help was Dr Achingliu Kamei, a PhD professor from Delhi University, who mentored me for this novel. She is from Lungkao, which is the village that Rani belonged to. She got me letters, photographs, books, and images which had information unreleased on the public domain. There are very few copies still in circulation of the above.”

Q: What preconceived notions did you have of Nagaland/Manipur that changed during your writing process?

“Firstly, that there are multiple tribes, and every tribe has a distinct, unique identity. You can’t mess with that; especially someone like me who is not from the Northeast. I soon realized I can only focus on a few factions who were directly involved in Gaidinliu’s story. So, the scope of this book is limited to Rani Gaidinliu’s fight for freedom from the British, and not the Zeliangrong struggle that followed after independence, which she also spearheaded.

“Also, because I’ve not visited the area much, I thought everything there would be hilly. That is not so. In fact, I realized there was a lot of acrimony between the ‘hills’ and the ‘plains’ people; something which the British exploited to the fullest extent. Today, we see this playing out in the Manipur conflict as well, leading to destruction and loss of lives.”

Q: Can you tell us the scope of your book: The 13-Year-Old Queen And Her Inherited Destiny?

“My book is focused on two major things that the British introduced; pothang bekari and pothang senkhai. Pothang bekari is the enforced house tax of Rs. 3 per month, even if one is unemployed. Senkhai is when anyone from the British Raj comes to the village, the villagers have to provide them with food and lodging. The locals were made to work as porters as well.

“It begins with a character named Masuangphui. He is whipped mercilessly by the British soldiers, because he refuses to comply with the pothang senkai rules. Similar incidents in and around the village lead to a spirit of rebellion within the young Nagas. Masuangphui is depicted as the son of a fortune-teller named Houdoliu. There’s no such fortuneteller in reality. But there might as well be, because seers abound in that part of our country.”

Q: Can you tell me more about this line between truth, fiction, and fantasy?

“The reason I wrote this book in ‘fantasy fiction’ and not just ‘historical fiction’ was because of the beliefs that surround Rani Gaidinliu and Jadonang. People truly believe they could heal people and bring them to life.

"For example, there is a recorded incident of Jadonang entering Bhubon Caves. He gets a revelation from the Python God Hechawang, who grants him power. Hechawang is said to be a tricky god. His power can be good or evil depending on how one prays to him.

“Now, when you talk to people in Manipur, they will say this is true. It is not legend for them, it is factual. Therefore, I have recounted it as I hear and read things. You will find a lot of folklore in the book. It is a testament to the beauty and mystique of Nagaland.

“But why did Jadonang travel to Bhubon Caves? That answer is not recorded anywhere. So, what I did instead was introduce Jadonang’s father. He dies at the start of the story, and that gives Jadonang a lifelong angst and a purpose to drive the British from his country. In the middle of the book, he starts getting trances and visions of entering a cave. But this bit is imagined. There are very few accounts of Jadonang’s father.”

Q: Did you include any fantastical elements that were not corroborated by facts/legends at all?

“Only one. I just extended the powers of the Python God! The python had possessed Jadonang first. I showed that Jadonang could summon snakes at will. This bit is not in the legends.

“Rani Gaidinliu gets powers after the transfer of command happens. Suddenly, only Rani can hear the python’s voice in her head, not Jadonang. This is to show how Rani is supposed to be the actual messiah, while everyone thought Jadonang was the one. However, these events are corroborated by the fact that there are incidents and dreams that declare Gaindinliu as the leader. I extrapolated them in a way that could be better understood by the readers.”

Q: Why did you choose to change the names of the characters? For instance, Gaidinliu’s name is ‘Dijeanliu’ and Jadonang’s name is ‘Dikanang’.

“Primarily, because I am not from there. I took a fable and researched it to death, but I did not want to toe the line. That’s the same reason why Nehru’s name is not changed in the book.”

Q: What do you think is the future of Rani Gaidinliu?

“Sometimes, I see Gaidinliu as a Chhota Bheem figure. There are a lot of similar ideas there. Their legends began at a young age. They were raised in an environment where the animistic movement is strong; where they are close to animals, nature, and don’t like foreigners exploiting the virgin land for themselves. I’d be interested to see Rani’s story head in that direction!”

Comments